Joy Wetzel, SCA Interpretive Ranger

Does your garbage bin frequently come close to overflowing? Do you hate having to buy expensive fertilizer for your garden? Are you constantly dealing with soil erosion in your backyard? If I told you there was an inexpensive and effective at-home way to resolve these problems, all while reducing your carbon footprint, would it sound too good to be true? Fortunately, this solution is real, and it’s called composting.

What is Composting?

Composting is a method of recycling organic waste into fertilizer with the help of fungi, bacteria, and insects. Organic waste is anything biodegradable that once came from a living thing (for example: food scraps, yard trimmings, paper, and manure). Through composting, you can return these materials to the earth.

Why Should I Compost?

Here are just a few reasons why composting is a great choice for your household:

- Save room in your trash. By relocating your household’s organic waste, you’ll find your garbage can at lower risk of overflowing.

- Give back to Mother Earth. Composting is the earliest form of recycling. All your organic waste came from the earth, and you can return it to the earth.

- Add nutrients to your soil. Say goodbye to buying chemical fertilizers and expensive soil additives.

- Reduce landfill waste. When organic waste decomposes in a landfill, it emits methane, a greenhouse gas. Composting significantly reduces those emissions and puts these waste materials to good use.

- Reduce erosion. Compost helps soil better retain water, encourages plant growth, and alleviates soil compaction. All of these effects help reduce soil runoff.

- It’s Fun! In a world where we send our trash away the second we’re done with it, it’s not often that we get to watch nature do its work. A compost pile is a never-ending science experiment that can fascinate people of all ages.

Ingredients for a Healthy Compost

At Bear Brook State Park, where the SCA New Hampshire Conservation Corps is based, a healthy compost pile requires a careful balance of several ingredients:

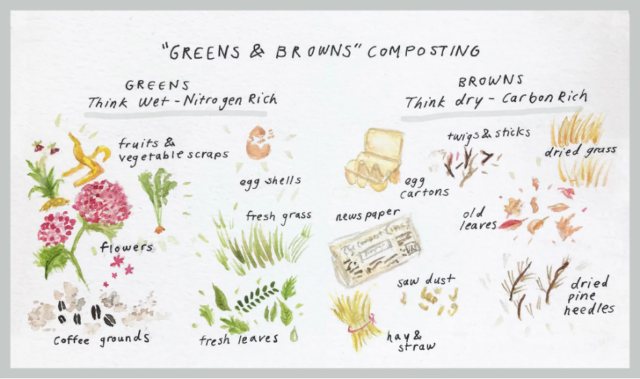

- Nitrogen-rich material, A.K.A. “Greens.” These materials are typically a lot moister and a lot smeller. Some examples of “greens” are: vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, lawn clippings, and used tea bags.

- Carbon-rich material, A.K.A. “Browns.” Some examples of “browns” are: cardboard, paper, dried leaves, and eggshells.

- Fungi, Bacteria, and Insects, A.K.A., the F.B.I. These are the living things that feed on and break down your organic waste. They give off heat as they do so, which is why a healthy compost pile is typically between 130- and 150-degrees Fahrenheit. Insects eat waste and excrete (poop) it. They also aerate your compost as they move around. Some people purchase worms to add to their compost, but they often make their way into the compost on their own.

- Oxygen. The F.B.I. need oxygen to perform their vital functions, so a compost pile will never thrive in an air-tight container. In many cases, this also means you may need stir your compost manually.

- Water. The F.B.I. also need water to live. A healthy compost pile should be moist, not wet, and have the texture resembling that of a wrung-out sponge.

Your compost should comprise approximately one part “greens” to three parts “browns.” Use the lasagna method when adding to your pile, layering the two types of materials and finishing with “browns” to avoid attracting wildlife.

What Not to Compost

In addition to knowing what must go in to their pile, a successful composter must know what to keep out.

- Inorganic materials. The F.B.I. cannot break inorganic materials down. This means avoid adding any metals, plastics, glossy papers, or anything chemically treated.

- Pesticides, fungicides, or herbicides. Plants treated with these chemicals will contaminate your compost and anything you attempt to grow in it later on. They are also likely to kill the F.B.I. that help break your compost down.

- Animal byproducts. Materials such as meat, dairy products, or pet/human waste give off strong odors that will attract wildlife and make your compost pile a nuisance.

- Oils. Oils also won’t break down properly, and they’ll throw off the moisture levels of your compost pile.

- Baked goods. Cooked grains and sugars can encourage bad bacteria growth and attract wildlife.

- Naughty plants. Avoid adding any plants that died of fungal or bacterial diseases, as this will allow these diseases to spread. You also want to avoid giving invasive species the opportunity to germinate in your compost. For more information on invasive plants, visit Ranger Becca Leone’s DPP blog post, “Invasive Species in New Hampshire to Watch.”

- Compostable plastic bags. This may initially appear counterintuitive. Unfortunately, most compostable bags sold in stores have fine print specifying that they are only compostable in commercial facilities. This means that they need to reach higher temperatures than possible in an at-home compost pile in order to decompose.

Choosing a Method

As you choose your composting method, begin by asking yourself some key questions:

- How big is your household? This will determine how large your pile needs to be.

- What do you plan to compost? If you just plan on composting food scraps, your pile can be a lot smaller than if you also plan on composting materials such as yard waste.

- Where do you live? It is important to consider how much room you have at your disposal. If you live in a more rural area, you will likely need to protect your compost from wildlife.

- What is your budget? Composting containers can run from almost no-cost to pretty pricey.

Once you’ve answered these questions for yourself, you can look determine what container works best for your compost.

- Compost piles. This works exactly how it sounds: clear a patch of bare ground in your yard and add layers of organic materials, being sure to alternate between “green” and “brown” layers. One drawback to this method is that your compost will be vulnerable to animals if not covered with chicken wire or other deterrents.

- Compost bins. These containers are easy to work: you simply add waste to the top and let nature do its job. They generally work more slowly than others, because they are less aerated, but you can speed up the decomposition process by stirring their contents. Stationary compost bins are available for purchase, but you can also make one yourself from a variety of materials, such as crates, buckets, wire fencing, pallets, trash cans, or even old furniture.

- Tumblers. These are containers that can be rotated, so you can stir and aerate your compost without having to touch its contents. They are generally considered much neater than bins, but they can be pricey. Because they are not open to the ground, you may want to add worms and other insects to them yourself.

- Food waste digesters. The bottom section of a food waste digester is buried underground, while users add their organic waste to the exposed section. This exposed section is often cone-shaped to concentrate the sun’s rays and heat the digester’s contents. These are a great choice if you do not plan to use your finished compost for gardening, because much of the decomposed material seeps into the ground as liquid.

- Counter-top processors. Disclaimer: these processors do not decompose your organic waste as a compost pile would. Instead, they dehydrate it and grind it into tiny pieces that can be used as fertilizer. These can be pricey, but they’re a good option for people who lack access to an outdoor composting space.

- Outsourcing your compost. If none of these options works for you, you can also see if any businesses in your area (such as organic farms) accept household organic waste. Some local municipalities also offer compost drop-off services.

Compost Troubleshooting

Composting is a complex process, and running into problems is extremely common. Please don’t fell discouraged! Here are some tips for troubleshooting a troublesome compost pile:

- My compost is too wet. You may need to add more carbon (“browns”) to your pile. Ensure that you’ve located it in a well-drained area.

- My compost is too dry. Your compost may need more nitrogen (“greens”). If you don’t currently have access to more nitrogen-rich materials, you can also just add more water. Ensure that your pile does not spend too many hours of the day in direct sunlight.

- Nothing is happening! Your pile may be too small to reach its optimal temperature. Try to collect more materials—ask your neighbors if they have any extra food scraps they’d be willing to share.

- My compost smells terrible! A healthy compost pile should have a pungent, earthy smell. If it smells more like a dumpster, your compost may be too wet or need a good stir. It may also have the wrong materials in it. Make sure you haven’t added any animal by-products by mistake.

- Animals keep going after my compost pile. These animals are attracted to the smell of your compost. First, make sure no animal by-products have been added to it by mistake. If animals are still causing problems, you can protect it with a secure lid or by wrapping it in chicken wire.

Conclusion

During a time when many of us feel powerless to combat climate change, it’s extremely important to remember that every little positive act matters. Composting is just one of many ways to give back to our planet. Like every natural process, composting takes a lot of time and patience, but it can be incredibly rewarding. Allow yourself to play with your composting methods, treat this as a learning experience, and marvel at the circle of life as it takes place right in your compost pile!