Joy Wetzel, SCA Interpretive Ranger

As Thanksgiving once again approaches to usher in the holiday season, disputes regarding the ethics of Thanksgiving are sure to resurface. Giving thanks is not an intrinsically political act, nor is it strictly American. Harvest festivities are practiced around the world. For instance, the Chinese Mid-Autumn festival has a millennia-long history; Canada’s Thanksgiving has nothing to do with pilgrims. Those of us who associate Thanksgiving with turkey, football, and parades, may struggle to understand why such a holiday is up for debate.

However, engrained in American Thanksgiving is a narrative that distorts our understanding of the early interactions between English colonists and New England’s indigenous people. The story of happy Indians and pilgrims coming together for a feast to celebrate their enduring friendship, appealing as it may be, fails to recognize the injustices that Indian Americans faced then and have continued to face in the following four centuries. As a result, many people choose to shun the holiday altogether. Other Americans are seeking to celebrate it in a more conscientious manner. Though this will be different for every family and community, I will be offering some suggestions for enjoying Thanksgiving while honoring New Hampshire’s indigenous history.

I want to first acknowledge New Hampshire is located on the ancestral and unceded land of the Abenaki people. The Abenaki people have resided in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine, which they refer to as N’dakinna in the Abenaki language, for around 10,000 years. They maintained a sustainable relationship with the land until it was disrupted by colonialism. European subjugation greatly reduced their numbers, but Abenaki communities remain active across this region. As a member of the white settler race myself, I can only provide a certain degree of perspective and must always open myself up to new learning opportunities.

Deconstructing the Thanksgiving Myth

We can begin by re-examining what we know about Thanksgiving. The Thanksgiving story which most Americans are familiar offers an incomplete picture of a highly-complex intercultural exchange. Rather than on the ship Mayflower, this story begins earlier, with a Wampanoag man named Tisquantum. Tisquantum, sometimes referred to as Squanto, was a member of a coastal village near Cape Cod, where Europeans had been trading with indigenous people for several years. In 1614, a British lieutenant kidnapped, planning to him to sell into slavery in Europe. Tisquantum ended up in England, where he learned English and was able to arrange passage back to the New World on a fishing vessel in 1619. However, when he finally returned to his village, he found it abandoned.

Infectious disease brought over from Europe had swept across coastal New England while Tisquantum was away, killing roughly ninety percent of its indigenous inhabitants. Suddenly, the community to which Tisquantum had fought to return no longer existed. Before long, he was captured again, this time by Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy, who found his proficiency in English suspicious. Massasoit decided that Tisquantum could be of assistance to his people. In addition to foreign invaders and a devastating plague, the Wampanoag Confederacy faced hostility with the neighboring Narragansett people. They desperately needed allies.

In 1620, the passengers of a ship called Mayflower established Plymouth Colony in Tisquantum’s now-empty village. Many early settlers were shocked by the abundance of resources they saw upon arriving in New England. As a result, they often entered the cold season grossly underprepared, failing to realize that winters in New England would be far harsher than what they experienced in Europe. Plymouth Colony was one of those groups. Only 52 of the 102 passengers lived through their first winter, but only by looting abandoned Indian villages for supplies.

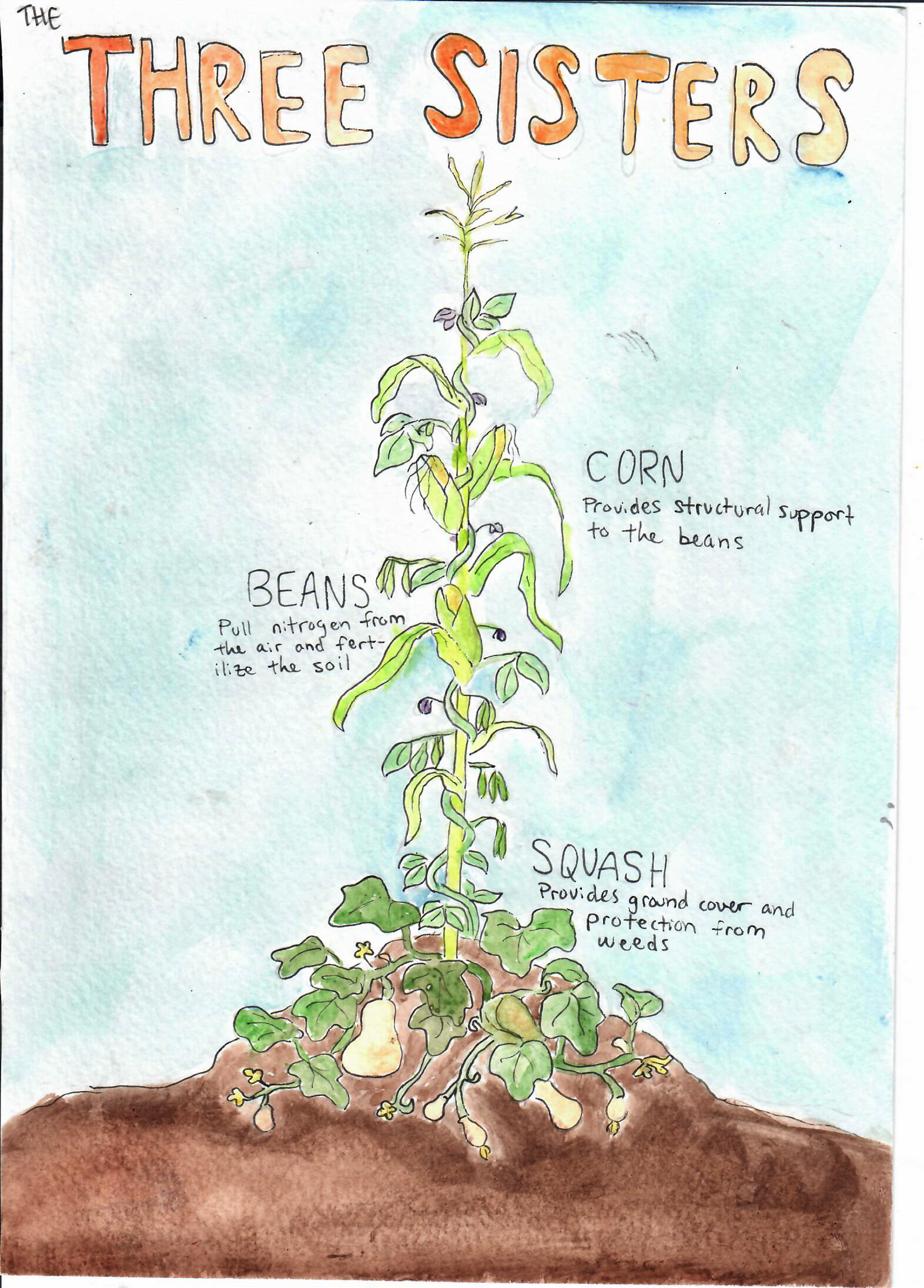

Massasoit believed he could ensure his people’s survival by establishing a relationship with this colony, and he employed Tisquantum as his translator. In the spring of 1621, Massasoit and his men approached Plymouth Colony to propose a deal. In exchange for information on how to survive in the New World, the pilgrims were to ally with the Wampanoag against the Narragansett. Just as the old story goes, this involved planting a lot of corn, beans, and squash.

By the fall of 1621, Mayflower’s passengers felt settled enough to host a feast of thanksgiving for their survival. They fired their muskets into the air in celebration, prompting around ninety of Massasoit’s men to come investigate. They were then invited to share the meal with the settlers. Tragically, Tisquantum succumbed to disease just one year later. The alliance between Plymouth and the Wampanoag did not last, and settlers continued to arrive on their shores en masse.

Though the first Thanksgiving took place outside of New Hampshire, similar interactions occurred across New England during the early-seventeenth century. Some indigenous groups may have provided assistance to nearby settlers out of genuine altruism. However, their situation was far more complex than the stories we traditionally tell let on. If you would like to share a more indigenous-focused version of the Thanksgiving story with your children, Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story is a beautifully-illustrated picture book that celebrates Wampanoag’s reciprocal relationship with their land without overlooking the need to mourn those lost to imported disease. Follow the link below to purchase it from an indigenous bookseller.

In the Spirit of Sharing

Thanksgiving is a celebration of endurance, often in the face of adversity. One of the best methods of honoring indigenous people in the United States is directly sharing resources. For instance, consider turning donating into one of your new Thanksgiving traditions. There are numerous nonprofits and collectives dedicated to indigenous empowerment across the country. Here are just a few:

- The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) is a non-profit that provides legal support and representation to indigenous people and tribes, ensuring that the U.S. government upholds and respects their tribal sovereignty. Learn more here.

- The Native Land Conservancy is dedicated protecting native ecosystems in coastal New England. Some of their projects include nature walks that promote indigenous perspectives and history of the land. Learn more here.

- United American Indians of New England (UAINE) campaigns for state legislature in New England that benefits indigenous people and advocates for the abolition of Columbus Day. They have hosted a National Day of Mourning on Thanksgiving in Plymouth, Massachusetts every year since 1970. The UAINE has also published a guide to supporting the National Day of Mourning.

- The First Nations Development Institute is a nonprofit that provides economic assistance to numerous indigenous programs across the U.S. According to its website, First Nations is the highest-rated American Indian nonprofit in the country. Learn more here.

You can also research advocacy groups in your community that would benefit from your involvement, be that through financial assistance, volunteering, or signing petitions. For instance, you can join the nationwide effort to rename Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day. While some states have succeeded in doing so, such legislature failed to pass in New Hampshire as recently as 2023. You can help the cause by contacting your local elected officials.

Mourn the Lost

New England’s early settlers only began laying claim to the region after epidemics killed the majority of its original inhabitants. Those lost to disease and genocide deserve our recognition, especially on Thanksgiving. So do the people who survived and helped settlers navigate life in the New World; they often faced fatal consequences for doing so. Their lives mattered, as do the lives of indigenous people across the world. Gratitude and grief are not mutually exclusive emotions; we can process them simultaneously. Take some time on Thanksgiving to honor the dead.

Incorporate Indigenous Cuisine

Much of what we consider traditional Thanksgiving food has its origins in New England: turkey, corn, squash and cranberries are all native to the area. However, many current staple ingredients of the American diet, such as potatoes, broccoli, and ham, only arrived North America during European settlement. Instead of relying on imported goods, you can give thanks to the land that provides for you by basing your meal around native and locally-harvested ingredients. Try to eat what is in season! In doing so, you continue the culinary traditions that have existed in New England for thousands of years. Some other native ingredients you can incorporate are: maple syrup, beans, Jerusalem artichoke, lobster and hazelnuts. Buying from local farmers also benefits your local economy and reduces the amount of pollution released from transporting products across great distances.

Add to Your Reading List

Honor indigenous history by educating yourself! Below are just a few of the books concerning New Hampshire’s indigenous history that I read this year.

- Keepers of the Earth: Native American Stories and Environmental Activities for Children,by Joseph Bruchac and Michael J. Caduto. Written by an Abenaki author, Keepers of the Earth is one of a series of books that retell indigenous folktales from around the United States. Each story is accompanied by a kid-friendly environmental science lesson.

- Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600-1800: War, Migration, and the Survival of an Indian People, by Colin G. Calloway. A detailed and thorough history of the Abenaki people post-European contact.

- A Time Before New Hampshire: The Story of a Land and Native Peoples, by Michael J. Caduto. This book offers a broad range of information on New Hampshire’s pre-European-contact history, beginning with the creation of the planet. Caduto also includes a simple guide to Abenaki pronunciation, an epilogue written by a councilman from the Abenaki Nation of NH, and numerous detailed maps and images.

- The Visual Language of Wabanaki Art, by Jeanne Morningstar Kent. Great for art lovers, this book examines pre-contact to contemporary art by artists of the former Wabanaki Confederacy. Kent looks to a variety of media, including birchbark, beadwork and weaving for a deeper understanding of their cultural symbolism.

Moving Forward

Finally, remember to give thanks year-round. Appreciating our communities, our families, and our local ecosystems, can be an everyday practice. Without our natural resources, we cannot survive. Hence, the plants and animals that sustain us deserve our respect. This understanding is integral to Abenaki culture, and it is something that all Americans can stand to learn.

References

Associated Press. “Native American tribes are gathering in Plymouth to mourn on Thanksgiving.” NPR, 25 November 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/11/25/1059212893/native-american-tribes-are-gathering-in-plymouth-to-mourn-on-thanksgiving.

Caduto, Michael J. A Time Before New Hampshire: The Story of a Land and Native Peoples. Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2003.

Mann, Charles C. “Native Intelligence.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2005. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/native-intelligence-109314481/.