Joy Wetzel, SCA Interpretive Ranger

For centuries, Mount Monadnock has served as a source of inspiration for countless artists and writers. These creatives can encourage us to see the mountain with a renewed sense of wonder. Today we will be exploring some of the most famous individuals who interpreted one of New Hampshire’s most popular natural landmarks through their work. We will also examine some ways that you can make your own Monadnock-inspired work of art.

Monadnock in the Visual Arts

Who knew that there were so many ways to depict one mountain? So many factors contribute to these varieties: season, time of day, location, skill level, and even the mood of the artist. Below are just two prominent artists who visually rendered Mount Monadnock during their lifetimes. As you read about them, consider all of the thought that they put into creating their artworks. Why do you think they chose to paint Monadnock, of all places, and what do you think they learned (about themselves and about the mountain) in the process?

William Preston Phelps (1848-1923) is often referred to as “The Painter of Mount Monadnock.” He was born in New Hampshire and studied art in Germany, but he only began painting the mountain after returning to his family homestead to care for his aging father. He is thought to have painted the mountain over one hundred times. Can you imagine having a landmark so important to you that you would paint or draw it over one hundred times? If you look closely at the painting below, you may notice that far less trees surrounded the mountain in Phelps’ time than today, because of heavy logging that had taken place during early European settlement.

While artists such as Phelps were known for painting Mount Monadnock, others sketched when they needed inspiration for their other work. Although Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849-1921) is best known now for his portraits of women, he frequently painted Monadnock and often hiked the mountain during breaks from painting his major commissions. Thayer grew up in Keene, New Hampshire. He was a dedicated reader of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was also drawn to Mount Monadnock. When developers attempted to purchase the mountain in 1911, Thayer was staunchly opposed and fought for its protection. After he died, he had his ashes spread on Monadnock’s summit.

The painting below is less detailed than Thayer’s other work, likely because he created it for himself, rather than for a paying client. However, his talent shines through in other ways: notice how he captures the effects of sunlight on the snowy summit with just a few brushstrokes.

Monadnock in Literature

The experience of summiting—or even viewing from afar—a mountain as grand as Monadnock is as exhilarating as it is difficult to describe. No wonder so many writers have tried their hand at capturing the awe that its magnitude and barrenness inspire. They incorporate a variety of figurative language, comparing the mountain to ship’s mast, a cathedral, or even a Titan. Does this mountain remind you of anything else when you look at (or from) it?

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was a poet, writer, and conservationist best known for his book, Walden. He loved the American wilderness and climbed Mount Monadnock four times in his lifetime, often camping near the summit. Thoreau was highly eccentric and considered an outcast during his life, so he may have felt a close connection to the mountain, whose name in the Abenaki language translates to “one that stands alone.” He sometimes went on what he called “beeline hikes,” where he would pick one direction and try to walk in as straight a line as possible, refusing to follow established paths or go around any obstacles he encountered. While this was an interesting approach to hiking, New Hampshire State Parks prohibits deviating from marked trails because of the damage it can inflict on sensitive ecosystems.

Below is an excerpt from his 1843 essay “A Walk to Wachusett,” in which he describes his feelings when viewing the mountains north of his home in Concord, Massachusetts. Though trees obstruct one’s view of New Hampshire’s mountains from Concord today, heavy logging-induced deforestation in New England during Thoreau’s lifetime made it possible to see Monadnock from much greater distances.

Excerpt from “A Walk to Wachusett,” by Henry David Thoreau

With frontier strength ye stand your ground,

With grand content ye circle round,

Tumultuous[1] silence for all sound,

Ye distant nursery of rills,[2]

Monadnock, and the Peterboro’ hills;

Like some vast fleet,

Sailing through rain and sleet,

Through winter’s cold and summer’s heat;

Still holding on, upon your high emprise,

Until ye find a shore amid the skies;

Not skulking[3] close to land,

With cargo contraband,[4]

For they who sent a venture out by ye

Have set the sun to see

Their honesty.

Ships of the line, each one,

Ye to the westward run,

Always before the gale,

Under a press of sail,

With weight of metal all untold.

I seem to feel ye, in my firm seat here,

Immeasurable depth of hold,

And breadth of beam, and length of running gear.

You can read the full essay here.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was a transcendentalist poet, essayist, and friend of Henry David Thoreau. In fact, it was on his property that Thoreau lived while he wrote Walden. Emerson is best known for his essay in praise of personal freedom, entitled: “Self-Reliance.” He climbed Mount Monadnock at least once during his lifetime, but he had not yet visited the summit when he wrote the lengthy poem “Monadnoc” in 1846. An excerpt is included below. Do you find his decision to describe the summit without ever having seen it creative or overconfident?

Excerpt from “Monadnoc,” by Ralph Waldo Emerson

On the summit as I stood,

O’er the wide floor of plain and flood,

Seemed to me the towering hill

Was not altogether still,

But a quiet sense conveyed;

If I err not, thus it said:

Many feet in summer seek,

Betimes,[5] my far-appearing peak;

In the dreaded winter time,

None save dappling shadows climb,

Under clouds, my lonely head,

Old as the sun, old almost as the shade.

And comest thou

To see strange forests and new snow,

And tread uplifted land?

And leavest thou thy lowland race,

Here amid clouds to stand?

And would’st be my companion,

Where I gaze,

And shall gaze,

When forests fall, and man is gone,

Over tribes and over times,

As the burning Lyre,[6]

Nearing me,

With its stars of northern fire,

In many a thousand years?

You can read the full poem here.

The Most Important Artist…YOU!

Have you ever been to an art museum and noticed that many people spend more time taking pictures of the objects on display than really looking at them? Or, while hiking, you may find yourself closely observing your surroundings only when at scenic vistas. In today’s digital age, it can be extremely difficult to take the time to thoroughly examine the world around you. Translating your experiences into another medium, such as drawing, painting, or writing, can help you do so. Artmaking is just one way of slowing down and thoroughly processing what you see and experience. And, anyone can do it.

Everyone encounters the world in their own unique way and can contribute something meaningful to the long history of creatives who have lived in New Hampshire. Next time you visit a natural landmark like Mount Monadnock, you may feel motivated to create something yourself, and I encourage you to do so!

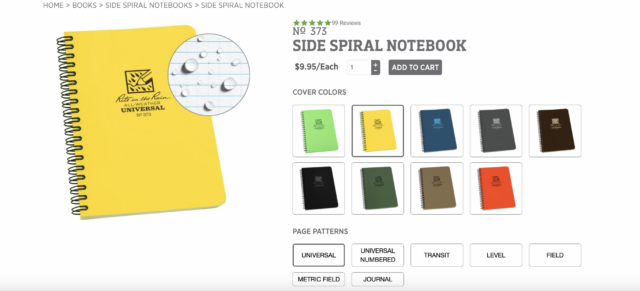

You may want to create a quick sketch or write a few lines while hiking. I always carry my journal in my daypack for this reason. If you are concerned about nasty weather, you may want to consider purchasing a Rite in the Rain waterproof notebook, which can be used in all kinds of weather conditions! If you want to write something but are lacking inspiration, try making a haiku (a three-line poem with five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third) or an acrostic (a poem in which the first letter of each line spells out a specific word). Even describing what you see in as much detail as you can makes for a fun creative exercise when exploring the outdoors.

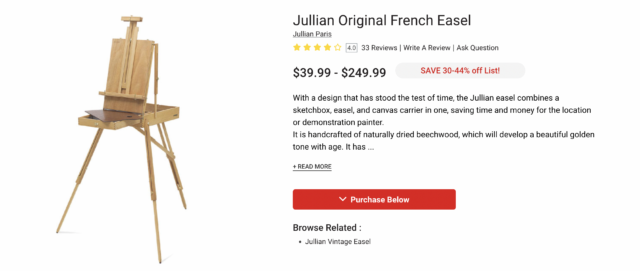

If you’re really dedicated, you could bring your work with you and paint en plain air. The French easel, which one can fold into a box and transport with relative ease, is a great resource for doing so. These were highly popular with famous Impressionist painters, such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, who preferred to paint landscapes in the outdoors, rather than under artificial studio lights. Watercolor paint is particularly easy to transport because of its light weight, but feel free to experiment!

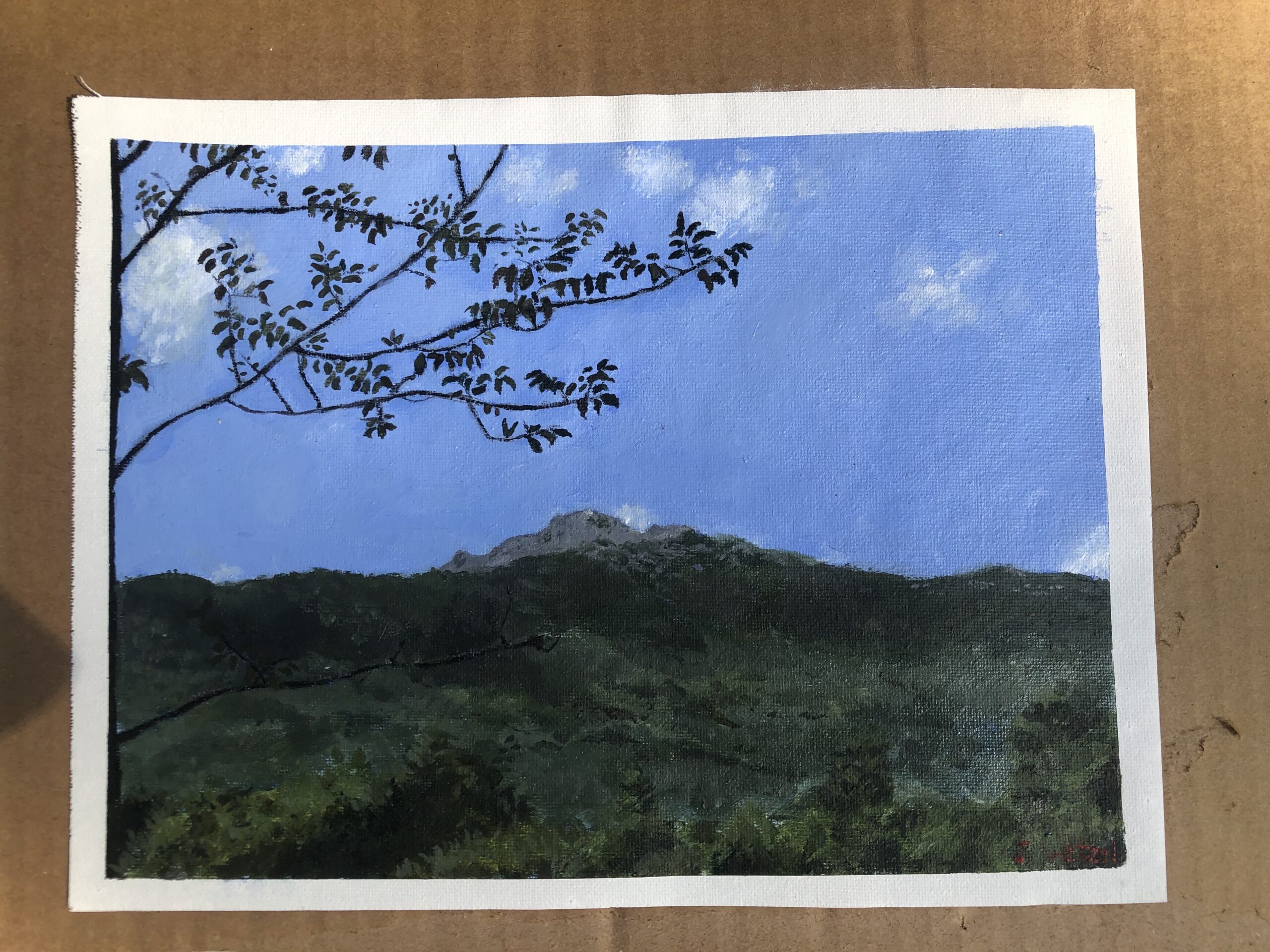

My favorite method is to simply take pictures of landscapes on my cellphone and use those reference images to paint at home. That way, I feel no pressure to finish a particular painting on-site, before the weather or light conditions shift. I recently took it upon myself to paint a picture of Mount Monadnock, based on a photograph I took at a nice vista near my cabin. I chose this particular composition because it was the first view of Monadnock I got when I moved to Jaffrey. My favorite (and the most challenging) part of the process was learning how to blend all of the different shades of green present in the composition.

Joy Wetzel, It Stands Alone, Summer 2023. Acrylic on Canvas.

Closing Thoughts

After reading this blog post, you may still feel no desire to create anything. However, I hope this discussion has motivated you to take a closer look at your surroundings as you experience New Hampshire’s natural landmarks, such as Mount Monadnock. There is beauty all around us, not just at the scenic vistas. Take note of all of the diverse plant and animal species you see. Listens to the birds. Pause to watch the leaves rustle with the wind. Most importantly, stay curious, stay safe, and have fun!

References

“Abbott Handerson Thayer: Mount Monadnock.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.166476.html.

Brandon, Craig. Monadnock: More than a Mountain. Keene, N.H.: Surry Cottage Books, 2007.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Monadnoc.” in Early Poems of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York, Boston: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company: 1899. https://emersoncentral.com/texts/poems/monadnoc/

Thoreau, Henry David. “A Walk to Wachusett.” The Boston Miscellany, January 1843. https://monadnock.net/thoreau/wachusett.html.