By Kendra Dean, SCA Interpretive Ranger

White Lake State Park and the surrounding area has a surprisingly rich history of how the local landscape was formed. From glaciers that carved mountains and formed lakes and bogs, to forest fires that provided unique habitat for local wildlife, and even to volcanic activity- this land has been shaped by some of the greatest forces of nature.

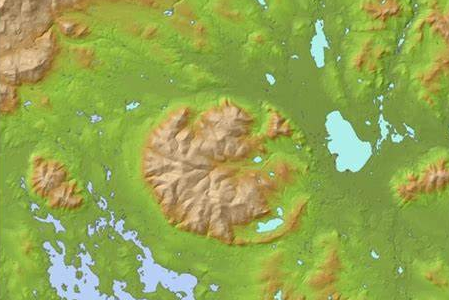

Let’s start with the volcano – no, it is no longer active – but it was 130 million years ago! This was during the Cretaceous period, when T. Rex was roaming around with those little arms. The base of the volcano was 9 miles wide, and the volcano itself was likely over 10,000 feet high- that’s a decently sized mountain! One day, the local tectonic plates shifted, causing the flow of lava to be cut off to the volcano, and leaving an empty chamber inside the volcano. Such a huge volcano couldn’t support itself under its own weight with the empty space: it collapsed in on itself, and scientists believe this took place within the span of a few days or even hours and would have been such a catastrophic event that the ash spread across the globe. There was still magma near the surface, and it squeezed up in a thin sheet, or “dike,” around the edge of the caldera that was left after the collapse. This formed the present-day Ossipee Mountain Ring Dike, one of the most visible and perfectly circular ring dikes in the world.

The Ossipee mountains – or really the singular mountain that now looks like several hills – that we see today were smoothed over by glacial activity. This was still a long time ago, but relatively much more “recently”.

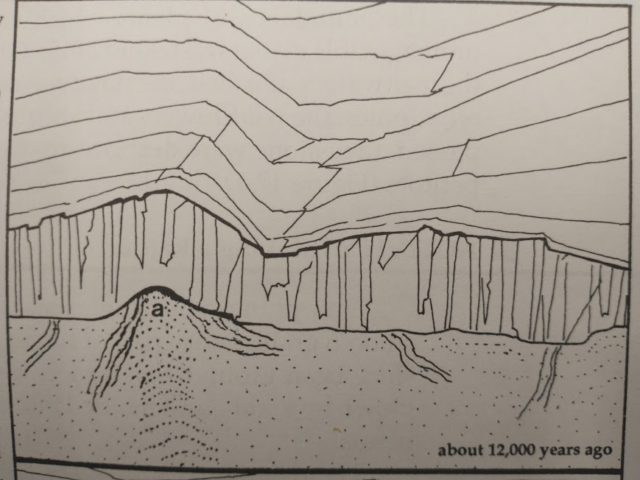

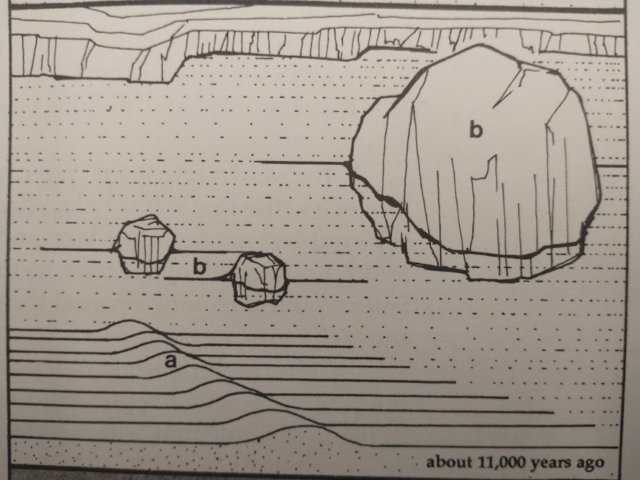

So, let’s fast forward several million years… Some people have asked me if White Lake is manmade- indeed it is not! This is a natural, glacial lake that formed about 10,000 years ago. Glaciers were going strong in New England about 12,000 years ago, and as global temperatures increased, they started melting. This took a while though, because these rivers of ice were big enough to cover the mountains we see today- sometimes over a mile high! If you venture up there, you might find glacial striations: stripes of ridges in the rock. As the glaciers made their slow retreat north, they gouged off softer rocks and left behind the harder bedrock of granite, leaving behind the mountains we see in the distance. Occasionally, chunks of ice would break off from the rest of the glacier, left behind to melt on its own. These chunks could be mega-chunks: and one of those mega-chunks is what formed White Lake.

When glaciers melt, rivers often form underneath, carrying sediments that the glacier picked up as it scraped along. As water flowed around the mega-chunk, sediments settled around it. Smaller sediments settled on one side of the ice chunk since the water could carry them farther. This is how the “white,” sandy beach that thousands of people enjoy each summer was formed. Once the ice chunk melted, it left a depression in the sediment that was left behind, which filled with water. Bodies of water that form in this way are called kettle lakes. Thus, we have our beloved White Lake.

Sometimes, the sediments build up underneath the glacier, and once the glacier has retreated, it leaves behind a mound of earth that we call an esker. If you want to find an esker near the park, follow the trail along the lake on the western shore until you see a small, white sign that reads “Pitch Pine Trail.” Follow this trail to a kettle bog. You will see a sign that says “Esker Trail” that you can follow.

The series of pictures below from Ned Beecher’s book, Outdoor Explorations in Mt. Washington Valley, illustrates the process of esker and kettle lake formations in the glacial outwash plain.

So, how about those little kettle bogs? Why aren’t they called lakes? The main difference between a bog and a lake is that bogs do not have inlets or outlets. The only way that these bogs retain water is from rainwater. This lack of flowing water causes acidity to build up, creating an ecosystem that few species care to live in. Sphagnum moss easily encroaches on the bog, hoarding nutrients and making the water even more acidic. The moss forms a sort of raft on top of the bog, with new moss growing on top of dead moss, which doesn’t decompose much due to the high acidity, and turns into what is called peat. The layer of peat grows thicker over time, creating a soil that allows other plants to take root, such as bog cranberries, black spruce trees, and carnivorous pitcher plants.

How does a plant evolve to be carnivorous? Since bogs have few nutrients, the plants that have adapted to live there have to be a bit creative. Pitcher plants and other carnivorous plants found ways to obtain nutrients other than soil: insects. Their red patterns attract insects to them, and tiny, downward-pointing hairs inside the pitcher help trap them by causing insects to lose grip and fall into the liquid inside. Digestive juices secreted by the plant dissolve the insects into the nutrients the plant needs.

The glaciers helped create another type of unique natural community called a pine barren. There is a 72-acre stand of pitch pines at White Lake designated as a National Natural Landmark, which you can walk through on the Pitch Pine Trail. Pitch pine trees are one of the plants that adapted to growing on sandy soil left behind from the glacial meltwater. This soil is poor in nutrients, hence the name of a “barren.” Pitch pines also adapted to the occasional forest fires that occurred in this post-glacial landscape: the seeds are released from their cones when exposed to fire.

The pitch pine trees you will see at White Lake are all mature trees. Wildfire management has prevented more seeds from being dispersed- the last fire to come through the area was in 1947, after which fires have been extinguished so as to protect property. There is a stand of pines, mostly a mix of pitch and red pines (which are also adapted to forest fires with their bark that can flake off in small pieces when exposed to fire), just outside the campground at the park, that is managed for timber and clearly shows the lack of younger trees.

To see a healthier pine barren, visit the nearby Ossipee Pine Barrens owned by the Nature Conservancy. Here, you will also see plenty of scrub oak, which takes advantage of the sunny spots between the pines. This place is protected due to the unique wildlife that lives here. There are some uncommon/rare species of moths here: Lithopane lepida lepida thrive on the abundance of pitch pines and red pines, while the sleepy dusky wing skipper loves to eat scrub oaks.

As you may have gathered, there is a bit of a dilemma over where to allow more of the pine barrens to become viable habitats for pitch pine trees and their counterparts, or to continue managing wildfires to allow recreation at the park to continue as usual. The lack of forest fires allows hardwood trees, such as maples and oaks, to creep their way into what was once a pitch pine paradise.

Whether the people who come to admire the trees, the mountains, or the sandy beach realize it or not, White Lake State Park and the surrounding landscape owes its unique beauty to those ancient forces of nature. As always, when visiting these beautiful spaces, be sure to do what you can to protect these natural communities and keep it beautiful by recreating responsibly and “Leave No Trace” (for more info visit Home – Leave No Trace – Leave No Trace (lnt.org)).

Resources:

Outdoor Explorations in Mt. Washington Valley by Ned Beecher

Exploring the Great Ring Dike Volcano–Full Version (youtube.com)