By: Eilís Donohue, 2019 Student Conservation Association New Hampshire AmeriCorps Member

As the snow melts and the weather slowly but surely warms towards spring, we at Bear Brook are getting ready to transition into a new season, too. For the past eight weeks we’ve been teaching science classes in local elementary schools, and, as I’m writing, we are beginning our ninth and final week. For the summer we’ll be splitting off, some of us doing conservation work and others doing interpretation at several parks around the state. Nearing a transition period, I can’t help but reflect on the season behind us and how much I’ve learned from teaching these young students.

The first week of our education season was observation week. We spent what would become our regular class times watching the students at work, talking to their teachers, and trying to get a sense of the culture of the school and rooms, the curriculum they already had, and what they’d like to see in our lessons.

Two things really surprised me: the general lack of science in the curricula, and what I (ultimately incorrectly) perceived to be the existing attitude towards nature. I saw chapter books for young readers titles phrased to inspire wariness of nature, about natural disasters, shark attacks, and so on. Wandering through the classrooms during observations, I perused some worksheets taped to the wall, introducing each student and some key facts about them, including their favorite colors, foods, and hobbies. Quite a few of them wrote that they liked to play outside and with friends, but a lot also wrote about video games, movies, and other indoor activities. Now I’m only 15 years older than these kids at most, but I wondered if the childhood experience could have changed so drastically since I was in third grade that kids didn’t like to play with bugs and sticks and mud anymore. Was this the attitude we were facing? Would our students be scared or bored or grossed out by nature?

Now as our final week of lessons draws to a close, I can happily say to myself from nine weeks ago that there was nothing to be worried about: these children are so genuinely excited by and interested in science and nature.

The general agreement among environmentalists is that the youth are the future in terms of conservation, reducing global warming, and generally saving the planet. That children need to be engaged and educated about nature is not contested; the big question is how to do best do it. I certainly don’t have the definitive answer after just a few months of teaching, but I do have some valuable takeaways that will shape my future attitude towards environmental education.

The beauty of this program is that each of the nine teaching teams was left, within certain parameters, to design the nine-week curriculum as they saw fit. The basis of everyone’s lessons was the concept of Earth as a system of four spheres: the biosphere (everything living), the hydrosphere (all water on Earth), the geosphere (rocks, soil, mountains, etc.), and the atmosphere. We were supposed to try to incorporate one or more of these into each lesson, and we were given past lesson plans as guidelines and sources of ideas. The other key concept that guided our lesson planning was focusing on place-based education—teaching about the environment that we all live in, rather than far-away lands.

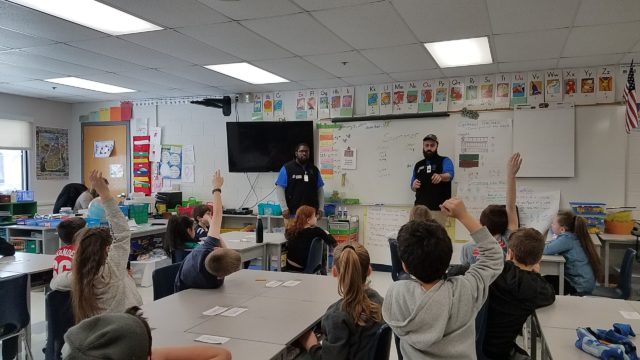

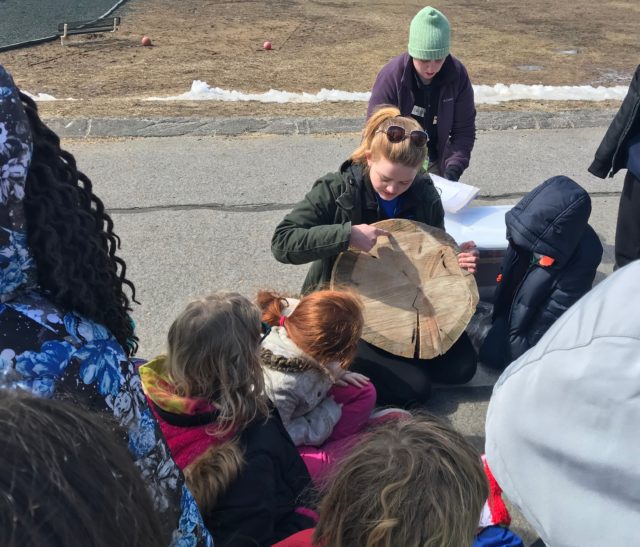

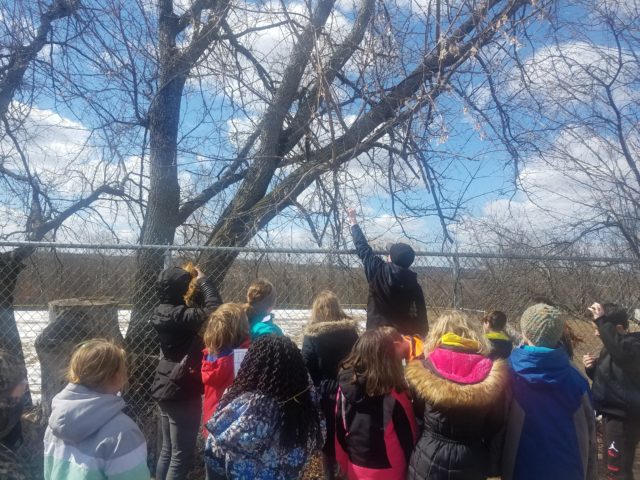

My team did get lucky with a lot of groups of bright students eager to hear what we had to say. However, we also worked hard to keep them interested and provide them with a wide range of information and activities, to try and reach the widest possible audience. Over the weeks, my team taught on a range of topics, including trees, geology, the water cycle, soil, endangered animals of New Hampshire. We also made sure to mix up the way we taught, alternating between games, crafts, lectures, journaling, and experiments, inside and outside the classroom.

It sounds cliche, but teachers often say that their students teach them just as much as the other way around. Here are a few lessons I’ve learned from teaching this season:

You won’t always be able to answer their questions, but that’s okay. Like most teams, we set up a question box for each of our classes, so they could write down nature questions they had for us while we weren’t around. They came up with some really interesting ones, some that we could answer right away, some that required research, and some that really threw us for a loop. Ultimately we tried our best to answer them all, but I think the best part of that experiment was just encouraging them to stay curious.

Enthusiasm goes a long way and can make up for a lack of expertise.The kids loved what we did, despite our team’s internal concerns about the flow of the lessons, cohesion week to week, and whether we were getting across all the information we ought to. They were always excited to see us, and to see what fun materials and activities we had for them that week. Seeing their genuine excitement made us equally thrilled to be there sharing our knowledge.

Keep ’em guessing. One of our most successful classroom management techniques was divide the lesson into parts amongst ourselves, then to position ourselves around the classroom so that when we were finished speaking, we would turn their attention to our teammate across the room. This meant the students were never sure who was going to be talking next, and had to physically turn and look; that, in combination with minimizing lecture time and the time that any one person was talking was often enough to keep them engaged.

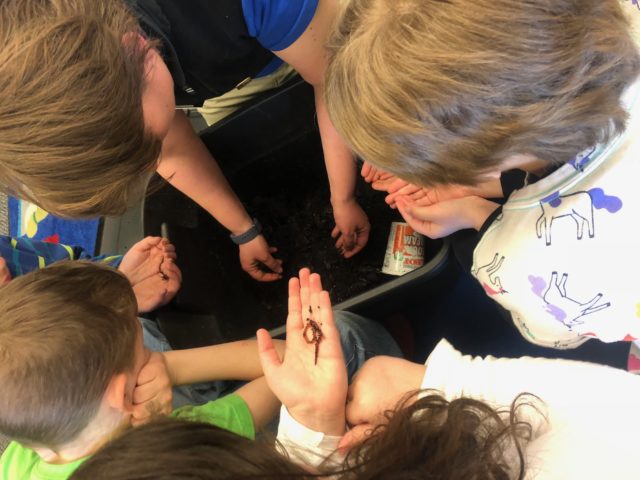

Kids love nature, period. It’s a mistake to think times have changed so much that children are no longer interested in playing outside, or that technology has made them less curious about their world. Technology can even be a way to connect their interests with things you want to teach them. That said, they’re also just happy to look at a rock for five minutes, or hold an earthworm in their hands.

We’ll shortly be moving into field trip season. Every class that SCA members taught will come to Bear Brook State Park for a field trip in May, where we’ll take them on nature walks, go ponding for macroinvertebrates and other aquatic creatures, and show them the park that’s become our home. I’ll miss teaching in the classroom, but I’m so excited to see what the children will think of our dear park. Hopefully they remember a thing or two from our lessons that they can recognize, but if not, that’s okay. If they remember anything we’ve tried to teach them, I hope it is a simple love of being outside—the rest can come later.