By Sarah Sherwood, SCA Franconia Notch State Park Interpretive Ranger and NH Corps Member

As New Hampshire’s preeminent state park, Franconia Notch attracts visitors from all over the world. Hikers tackle the Franconia Ridge Loop, skiers and boarders shred Cannon Mountain, and casual travelers take in the Flume Gorge and the Basin. Little do many of them know that they owe their experience to natural forces that shaped the area over millions of years.

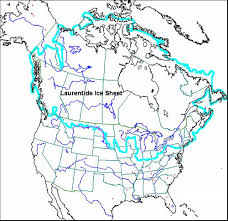

Franconia Notch was formed long ago as glaciers slid across what has since been named the state of New Hampshire. Beginning nearly three million years ago, the Ice Age brought colder, shorter summers, preventing winter ice buildup from melting each year. As the global temperature dropped, the Laurentide Ice Sheet formed, moving south from Canada into what is now called New England. As recently as 12,000-14,000 years ago, ice covered the White Mountains in sheets that could reach over a mile high – sometimes even higher than Mt. Washington! These cool giants used their massive power to carve the notch as we know it today.

“Notch” is merely a New England term for a deep valley, which is exactly what the glaciers created. As the Laurentide Ice Sheet pushed south, it sheared off the sides of mountains in the area, leaving behind a distinctive U-shaped valley with steep walls. This indicates to modern scientists that a glacier – and not a river – formed the valley, as rivers tend to cut V-shapes as they wash away soil and erode bedrock. The notch’s shape is the biggest hint to its origins, but other clues left behind by the glacier around the park confirm its past presence.

If one pays attention to the bare bedrock they’re hiking on in the mountains of Franconia Notch State Park, they might notice a peculiar phenomenon known as glacial striations. This is a fancy term that simply means scrape marks on exposed rocks in the ground. As the glacier traveled across the land, it picked up loose boulders as easily as we pick up sand, and sometimes these hitchhikers scraped against the ground as they glacier carried them by, leaving their mark in the form of deep parallel gouges. Geologists – and even casual observers – can use these striations to determine the direction of the ice sheet’s movement.

Occasionally, boulders carried by the glacier ditched their ride, getting left behind far from their place of origin. Today, they look randomly scattered, out of place in otherwise barren areas. We know they couldn’t have come from local rockfalls because they are composed of a different type of rock than the surrounding bedrock or mountainside. Known as glacial erratics for their irregular distribution, Franconia Notch boasts several beloved examples. Cannon Mountain was named for the cannon-shaped erratic on its summit, and Boise Rock is easily accessed by visitors from the interstate. Other odd boulders can be seen around the park, if one knows to look for them.

Many of the Park’s most popular attractions can also be attributed to glacial activity. The Flume Gorge is a unique geologic specimen that is viewed thousands of times every season. The Gorge began its journey when the Conway granite that comprises most of the area cooled and cracked in parallel lines. These fractures were then filled as basalt was forced up from the earth and crystallized into fine rock dikes. As the Ice Age came to an end and the glaciers started to melt and shrink, rivers of glacial meltwater torrented across the land. The water eroded the basalt faster than it did the granite, leaving behind the stunning, steep canyon walls that visitors enjoy today.

As the meltwater shaped the Flume, it was also creating the Basin not far away. Sediment, sand, and rocks carried by the large rivers of liquid glacier got caught at some point in a small pothole not far from where cars now travel the interstate. The water swirled, creating a small whirlpool that constantly ground sediment against the sides of the rock pothole, deepening, widening, and smoothing it. When the rivers died down sometime later, what was left was an uncommonly smooth kettle hole funneling a pleasant eddy of the Pemigewasset River.

Visitors who come to Franconia Notch State Park today often don’t realize that the striking shapes of Cannon Mountain and the Franconia Ridge are thanks to colossal sheets of ice that inhabited and defined the area for millions of years. If you visit the Flume Gorge, the Basin, Cannon’s peak, Boise Rock, or any number of destinations in the park, it’s nice to silently thank our cold, inanimate predecessors for creating the Franconia Notch that we know and love.

To learn more about Franconia Notch State Park’s geology, come stop by the Hiker Cabin at Lafayette Place Campground or attend one of Ranger Sarah’s “Glaciers: Movers and Shapers” programs!