You may know that the Abenaki are the local indigenous tribe on much of New Hampshire- but did you know that they were some of the first creators of the energy bar? That’s right, the original power bar was invented by indigenous people of North America. The name of this food comes from the language of Cree, which is one of the most common indigenous languages in North America, and pronounced pimîhkân– in the Abenaki language, it is pronounced as ‘pemmigan.’ In the Abenaki language, ‘Pemmi’ means fat, oil or grease, and ‘gan’ means something that is made. (A lot of English speakers today pronounce it as pemmican, but I will use the Abenaki word in this article.)

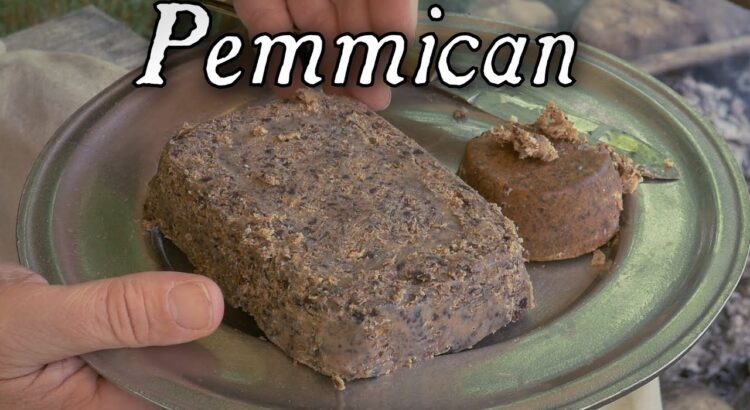

The fat of pemmigan usually came from big game animals that the Abenaki hunted, such as moose, bison, deer, bear, or fish. Traditionally, the meat of the animal was dried out by smoking it over a fire then ground into a powder. For large amounts of pemmigan, this was done by spreading out the dried meat on a tanned bison hide that was pinned to the ground and using big sticks to pound it into powder. Grinding between two rocks, like mortar and pestle, was another method. The fat from the animal was then heated and combined with the meat powder in a 1:1 ratio, so that the fat would permeate the meat to prevent moisture and bacteria from entering, giving the food a long shelf life. If prepared correctly, the pemmigan could last for years! The Abenaki would add spicebush to their pemmigan, a local plant with preservative properties and other nutrients, to help preserve it.

Native Americans sewed the pemmigan into bison hide bags for storage, and sometimes sold or traded large bags to European settlers. In the 18th century, pemmigan gained popularity amongst fur traders who wanted to travel light. Having a compact calorie content meant it was easy to transport, making it an attractive food source on long voyages on northern fur trade routes. One big bite of pemmigan can contain 100 calories! This was especially helpful in winter when food was scarce. However, the bars were not usually eaten on their own – they aren’t the yummiest energy bar. European settlers and fur traders often added pemmigan to a stew with water and flour, and sometimes wild onions and potatoes, which they called “rubaboo.” It was also fried with similar ingredients to create “rechaud,” as it was called in the West.

If you are interested in trying this historical energy bar, be sure to do plenty of research on how to prepare the meat. Or you can try a vegetarian version and substitute meat with local nuts and seeds (i.e. pumpkin seeds, walnuts, and pecans) and dried berries, such as cranberries, blueberries, strawberries and cherries. It can be stored in a cool, dry place for maximum shelf life at room temperature. Even though it can have a long shelf life, you may still want to store it in the fridge to be sure it doesn’t spoil sooner than you expect. Always check for signs of spoilage before eating anything that has been sitting around for an extended period of time.

Speaking of local foods… the Abenaki did not fully rely on pemmigan to survive the winters, by any means – they were able to gather, hunt, and preserve a large variety of food throughout the year, as depicted by this chart made by modern Abenaki.

You may notice that animals that were around year-round were not necessarily hunted heavily year-round- for example, in the spring and early summer, it appears that deer and black bears were not hunted, perhaps to allow a time of peace for mothers to raise their young. Unfortunately, some of the aquatic species (which may have been used in pemmigan) like the Atlantic Salmon and the freshwater eel, are not as abundant in New Hampshire as they once were. Atlantic salmon would swim inland to spawn, and they were such a popular fish to catch that commercial fishing completely depleted their populations in most areas. Today the only wild populations in the northeast are a few rivers in Maine. American eels would also swim inland from coastal rivers as juveniles (at which point they are called elvers). Their range has been limited by the construction of dams and are now mostly only found near the coast.

Eating food that is local and seasonally appropriate is a lesson we can learn from the Abenaki, without taking too much. Whether you’re making pemmigan or any other meal, I encourage you to source your ingredients locally so as to reduce our carbon footprint.

Resources:

Pemmican | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica

Atlantic Salmon Species Profile | NOAA Fisheries

American Eel | State of New Hampshire Fish and Game (nh.gov)