06.07.13

“We were left alone with the night hawks…their dry and unmusical, yet supermundane and spirit-like voices and sounds gave fit expression to this rocky mountain solitude…it was a thrumming of the mountain’s rocky chords; strains from the music of Chaos, such as were heard when the earth was rent and these rocks heaved up.”

– Henry David Thoreau, June 2, 1858. Mount Monadnock.

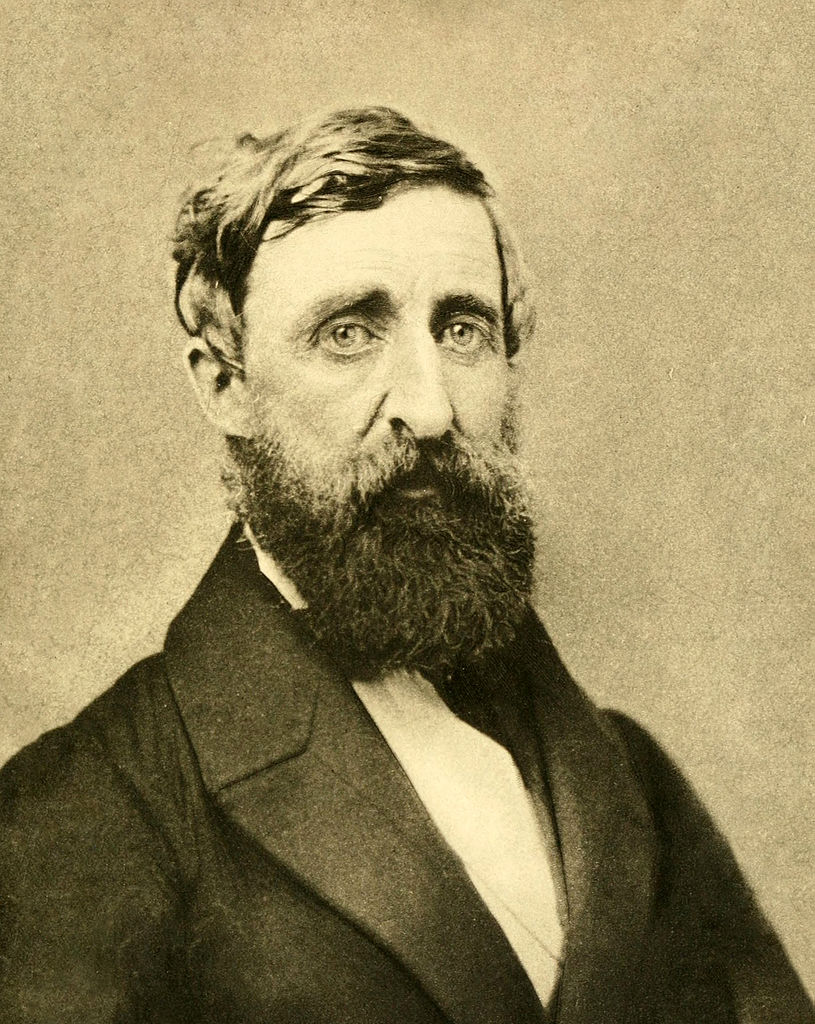

Absorbing the descriptions and thoughts of Thoreau, in any of his brilliant works, stirs feelings of wonder and joy and gives me a continusouly renewed appreciation for the natural world that is unmatched by any other author, except perhaps John Muir.

Coincidentally, on the political spectrum, as artists, Thoreau’s and Muir’s activism and writings have caused me to stand up, take notice, and take action, in just as much of an always hopeful, positive inspiration as given to me by the music and words of the Clash or the Dead Kennedys. John Muir? Joe Strummer? There are more parallels than you may realize. But, that is for another time and a whole other piece I am working on.

There will be more Thoreau to reflect upon later in the “history section” of this week’s Report. You did notice the date of his journal entry, did you not?

We have enjoyed a much steadier week of weather in the Monadnock Region this week. The mountain somehow dodged some strong thunderstorms last weekend, although the rain eventually came Sunday evening and carried into Monday. The skies cleared by Tuesday and temperatures hovered in the upper 60’s and low 70’s for the week.

It does not look like we will be as fortunate for the upcoming weekend. Today’s heavy rains will carry into Saturday morning. Cloudy skies and gusty winds are expected for the remainder of Saturday and passing showers could pop up on Sunday.

The beginning of next week looks to bring more rain. Sunday appears to be the best window to get a dry hike in, but the forecast is changing routinely, so check before you go! Temperatures should remain, at the base of the mountain, in the upper 60’s and low 70’s for the next few days.

Expect muddy, wet trails this weekend and bring some extra layers as it will be brisk above treeline.

The black flies have mostly clocked out for the season and it is now the mosquitoes’ turn to take an unwelcomed role in your hike. I would not say they are more abundant than usual, but they are present. If you’re a hiker who opts for “bug dope”, bring your spray along and be ready to have your patience tested at times. Their numbers will thin out as you move higher, out of wooded areas of trails.

This Week in Monadnock History

155 years ago, Henry David Thoreau made his third journey to Mount Monadnock, traveling to the mountain and camping on its southern shoulder with friend Harrison Blake, from June 2nd to June 4th, of 1858.

Grand Monadnock has long been a magnet, attracting and inspiring generations of artists, writers, painters, musicians, and photographers. The most well known admirer of our great mountain is arguably Henry David Thoreau, the famous Concord, MA Transcendtalist author, explorer, and activist. Thoreau visited Mount Monadnock four times in his life, camping for a total of 11 days.

One year before he began his infamous stay at Walden Pond, Thoreau first stepped foot on Monadnock in July of 1844, at the age of 27. There is little remaining documentation of this short visit, with the exception of a few remarks written years later. Thoreau returned to Monadnock for his second visit in September of 1852.

Thoreau’s third visit to the Region began on June 2nd, 1858. He took the 8:30am train from Concord, Massachusetts, picking up Blake at the stop in Fitchburg, and both arrived at the train station in Troy, NH (which still stands) at 11:30am.

Here are some notes from each day of Thoreau’s 1858 visit:

June 2:

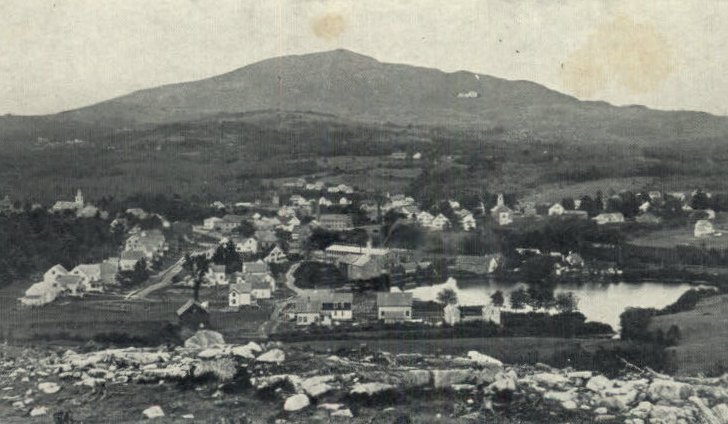

Almost immediately after leaving the Troy Depot, Thoreau mentions the mountain is in sight; “its sublime gray mass- that antique, brownish-gray, Ararat color.” On their hike from Troy to Monadnock, Thoreau mentions passing a school and was allowed to take a shortcut through an old man’s field, who was quite impressed with the size of Thoreau’s and Blake’s packs. The elderly man also lamented to them that he “shall never go up [Monadnock] again.”

As he often did on his adventures, Thoreau takes note of plants he is able to identify on the walk to the mountain (and even on the train ride from MA earlier). Eventually, they start climbing Monadnock, passing by the small house of Jospeh Fassett (foundation pictured above), who was “so busily at work inside that he did not see us.” Thoreau and Blake stopped to eat their dinner likely at the spot that is now known as Fairy Spring.

Thoreau and Blake saw a dozen people on their hike up and his journals mention the “very pleasant” conditions of the day. They ran into a man and a boy who were out hunting “pigeons”, but had “only killed five crows.”

Thoreau and Blake continued up and selected and prepared a campsite in a place that Thoreau estimated to be about a half mile from the summit. They cut spruce to create a shelter and beds. Camping and fires are no longer permitted on the mountain.

Thoreau and Blake then left their packs at camp and hiked/bushwhacked to the summit for sunset. On the way, Thoreau found a nest with three eggs and also “commonly” observed “rabbit’s dung”, in addition to identifying more moss and plants, including mountain cranberry.

Thoreau and Blake found the view to be too “hazy” and returned to their camp just before sunset, becoming lost on the way down. “…for nothing is easier than to lose your way here, where so little trail is left upon the rocks and ravines are so much alike.”

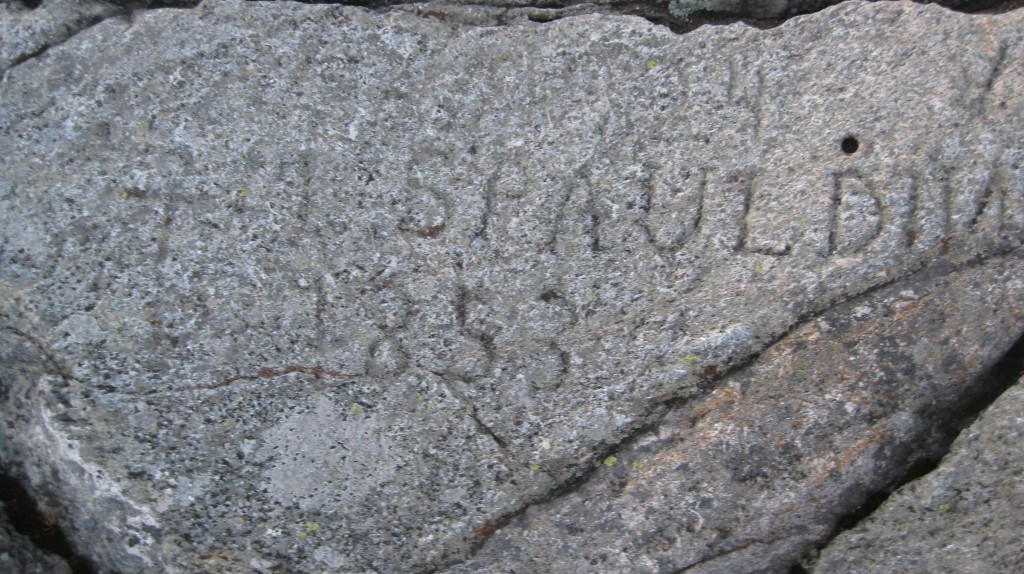

Before bed, Thoreau, referring to Monadnock as a “temple”, complained about the garbage left by visitors at the summit and the graffiti of the times; chiseled names in the stones.

Thoreau remarked that “you could not hire a stone-cutter to do so much engraving for less than several thousand dollars,” and brilliantly referred to the vandals as “false pretenders to fame”.

That night, Blake and Thoreau kindled a fire, then sat on a “rocky plateau” near the camp, “taking our tea in the twilight.” During the night, Thoreau thought he faintly heard a dog barking from the base of the mountain and Blake noted he heard a “bullfrog.”

Thoreau was awake by 1am, awoken by a “little bird”. He mentioned the sight of the moon and that on Monadnock, “every sound is a little strange there.”

June 3, 1858:

Disappointed in the conditions for sunset the night before, Thoreau and Blake instead tried for sunrise and breakfast at the summit, getting out of bed at 3:30am (would be 4:30am now, given “daylight savings”) having been awoken by birds, including a Junco and a Robin. It was still a bit hazy and the view did not reach as far as Thoreau would have liked, hoping to catch a glimpse of the White Mountains (90+ miles to the north).

Thoreau spent the morning exploring the upper reaches of Monadnock, taking inventory of plants, including one of my favorite spring flowers, the Rhodora.

Thoreau and Blake spent the entire day circumnavigating the upper elevations of the mountain at a pace in which he described as “slowly sauntering”, taking notes and inventory of the plantlife. Thoreau included a list of dozens of plants in his journals that were found “within a dozen rods” of the peak of Monadnock. For those who are not aware, 1 rod = 16.5 feet.

Interestingly in his journals on this date, Thoreau, without much of any background in geology, notes some key features of Monadnock, including identification of certain rocks and noting glacial scratches (and their direction of movement) on the mountain’s surface.

The bogs around the mountain’s shoulder proved to be of high interest to Thoreau as well and he spent much time exploring around them, and apparently in them, “sinking a foot into wet moss.”

Thoreau was also impressed with the condition and shape of the spruce trees on the ridgelines, which have obviously been influenced by the winds and weather.

After dinner, Thoreau and Blake hiked down the northeast shoulder of the mountain, nearby what would later become the Pumpelly Trail (blazed 30 years later). Thoreau talks of the great views of Jaffrey and Dublin from this side of the mountain and remarked that, what is now known as Dublin Lake, looked “worth to sail on.”

Their second night proved quieter than the first, although Thoreau complained a bit about the mosquitoes. Gathering clouds led the two companions to locate a nearby overhanging rock as a better shelter from the elements if their spruce boughs were “not tight enough.”

June 4th, 1858:

Thoreau and Blake arose from the slumber and began their descent at 6am traveling through Rindge, NH on their way to Winchendon, MA, opting not to hike over Gap Mountain to the train station in Fitzwilliam. During their departure, Thoreau looked back at Monadnock (probably often). “It is remarkable how, as you are leaving a mountain and looking back at it from time to time, it gradually gathers up its slopes and spurs to itself into a regular whole, and makes a new and total impression.”

Henry David Thoreau would return to Mount Monadnock for the fourth and final time in August of 1860. He would die from a bout with Tuberculosis in 1862.

Many followers of Thoreau think he would have written a detailed book about Monadnock, perhaps even a field guide of sorts, if he lived longer. He even appeared to be linking his 1858 journal entries to his previous 1852 Monadnock journals. Thoreau was one of the first people to intimately study and identify the plantlife and wildlife on Monadnock and his notes and observations have been used to present day, to evaluate how the mountain has changed.

Henry David Thoreau was strongly drawn to Mount Monadnock, like many of us are. Thoreau was obviously quite interested in studying Monadnock. He remarked that “those who simply climb to the peak of Monadnock have seen but little of the mountain. I have come not to look off from it, but to look at it.”

But, I whole heartedly believe Thoreau was not only drawn to Monadnock merely as a place to learn and study the natural world, but because he found something deeper at this mountain. The same inexplicable force that causes all of us to fall in love with Monadnock struck Thoreau too. Things like litter and graffiti might not have irked Thoreau the way they did if he did not view the mountain as sacred ground. I think Thoreau and Monadnock had a solid understanding of each other. And for those of us who love Monadnock, I think we have a solid understanding of Thoreau.

Reading through Thoreau’s journals has influenced me over the years to be more observant, to study my surroundings, and to take in the natural world with deeper breaths and pace closer to a “slow saunter”.

Thoreau is an American icon that will forever be tied to this great mountain. We are fortunate that Thoreau cared as much about Monadnock as we do and maybe helped us to understand the mountain, and ourselves, a little bit better.