The weather here at Mt Washington State Park, as many of you may know by following the Observatory’s conditions page, has been EXTREME since start of the New Year with thaws, cold snaps, lower than average snowfall, very hard/icy snow and peak gusts in the 115mph range. Despite this, winter climbers on the summit are ever more common, climbing in what we (guides or staff on Mt Washington) consider the severest we want to be out in: minus 20F with 80mph gusts. Only a few of the most prepared and experienced climbers are making the summit in these conditions. These are true mountain climbing enthusiasts with the latest clothing, good stamina and experience who can safely make the ascent via one of the 12 trails or numerous technical climbs. Aspiring climbers often take advantage of the Presidential Range’s Extreme Winter Weather to learn how to dress, navigate and safely move above tree line in winter. This training has helped many to safely accomplish significant climbs in the remote Great Ranges around the world like Baffin Island, Alaska, Andes and Himalaya.

Winter Hiking vs Winter Climbing

What is the difference between a winter hiker and a winter climber? Anyone who ascends above the tree line in winter, wearing full crampons and needing an ice axe is a winter climber. A winter hiker is someone who hikes in winter and does not need full crampons to make uphill progress or an ice axe to arrest a fall. Many of NH’s 4,000 foot peaks can be ‘hiked’ in winter but many also require ‘winter climbing’ at their summits. Snowshoeing in January up to the floor of The Great Gulf Headwall or to base of Tuckerman Ravine is considered winter hiking. Moving through steeper terrain, like The Lion Head or Ammonoosuc Trail, or Great Gulf Headwall is winter climbing. Traveling through the steepest terrain such as ice cliffs, requiring the use of ropes and belays for safety is technical ice climbing.

Recent Rescues

Sometimes even the most prepared and experienced climbers find themselves in danger. Just in the last month a handful of outdoor recreation rescues occurred, most which I know about first hand:

Ascents of Honor Film Crew

The 1st occurred with a much publicized fundraising event for a former Special Forces Marine with one leg to tackle a technical Huntington Ravine ice and snow climb to the summit of Mt Washington. Their intent was to film the climb and post pictures through various media outlets to raise awareness of the needs of families of disabled vets. It was and still is an awesome project! During their climb the team of 12 were caught in a slab avalanche near the top of Central Gully. The account of what happened was documented by the USFS Snow Rangers. USFS Snow Rangers are the lead agency in charge of Search & Rescue on this side of Mt Washington in winter months.

There will be much to learn about large group dynamics and risk analysis in the future as indicated by the film crew who indicated how their documentary now will focus on their accident on Mt Washington and the lessons to be learned.

Climbing Team in Kings Ravine, Mount Adams

Another rescue involved a missing climber in Kings Ravine on the North side of Mt Adams.

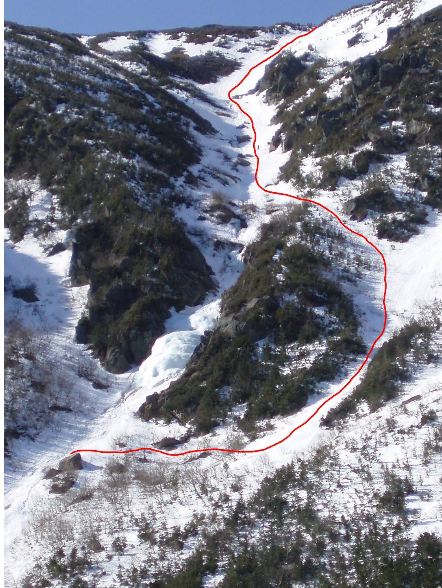

The party consisted of seven climbing buddies in their sixties, well equipped and experienced for the climb, having made numerous winter ascents of Mt Washington, Katahdin and western US peaks. They were prepared for ice climbing but didn’t like the conditions of the ice bulge in Great Gully and decided to take the snow gully to its right.

Group leader ‘Leo’ reported that their climb went up the center of the gully with perfect hard slab snow that was leaving a nice boot ladder. At the top of the gully five of the group continued straight up while the 2nd to last climber, Leo decided to exit the gully from a different route which was a little steeper, with harder snow, but a shorter exit to flat ground. The last in line, Richard, followed him. On the last few yards the snow was icy and wasn’t leaving boot imprints like the middle of gully. At the top, where it crested, ‘Leo’ looked back down to see how ‘Richard’ was doing and he was gone. Communication between Leo and rest of the party was difficult due to wind. It was also hard for the 911 operator to hear when Leo, over the wind, made an emergency cell call that a climber was missing.

Diane Holmes and I happened to be at Gorham Fire Station finishing training when Gorham dispatch called about a possible incident taking place in Kings Ravine. Knowing the Gully and the implications of what ‘gone missing’ could mean, we headed home to gear up. Diane made the calls to put Androscoggin Valley Search & Rescue (AVSR) team on stand-by.

Fish and Game (F&G) had most of their resources in Errol and Pittsburg area tending to the big snowmobile weekend (with 3 snowmobiles accidents to investigate that afternoon). F&G Lt Doug Gralenski called just as I was leaving for the trail and officially requested a Hasty Team and AVSAR support. He explained that a delayed response could be expected by F&G due to travel time. We had already called Caleb Johnson the Randolph Mountain Club Grey Knob Cabin caretaker and I planned to rendezvous with him on the ravine floor.

In the meantime AVSAR members were mobilizing resources to the Appalachia trailhead in Randolph. At trailhead we got the sad call that the climbers had found their deceased friend. I left behind medical gear and took up a rugged bag along with technical climbing gear and rope as we didn’t know if a lower was going to be needed. With three 2-way radios, (to talk to AVSAR, RMC and F&G) spare batteries, cell phone, lights and arctic survival gear, it was a heavy pack to move fast. The trail was packed so at least snowshoes could be left behind.

F&G told the descending climbers that they would be on their own for a while before anyone would be up to meet them and to do what they could to manage the scene. Caleb arrived on scene first to provide fresh horsepower and encouragement to the somber procession. The floor of King Ravine is a ‘rock glacier,’ strewn with giant boulders so there was as much lifting and passing as there was dragging.

I arrived close to the end of the boulder field with a much more slide-able plastic and nylon sack. AVSAR members Diane Holmes and Samantha Brady took up steering the tail end, trying to keep us pointed in right direction during the steep side hills. It was freezing cold but the hard work kept us warm.

About half hour later we could see several headlamps rapidly approaching. It was two members of F&G’s ‘Advanced Search and Rescue Team’ along with an Eastern Mountain Sports climbing guide with the Mountain Rescue Service. F&G carried up a packable two piece toboggan. Now, with a real sled and fresh manpower we took off down the trail working hard to keep up with the pace set by F&G and MRS. As more rescuers arrived we were grateful to let them take over recovery. We weren’t back at the trailhead until 7pm – about 6 hours after the first 911 call was made from the top of the Ravine.

No one knows why this climber fell. Did a crampon pop-off? A simple, tired trip, unable to ice axe arrest or medical issue? Richard fell an estimated 1,000 feet. In good snow years there have been similar incidents where climbers have also fallen the whole distance of the gully and survived thanks to soft snow at the bottom of the gully that not only provides a soft cushion but also buries the rock and tree hazards present during this lean snow year.

Expect the Non-Expected

We are all very sad and share our condolences with the family and friends of last month’s tragedies and wish a speedy recovery for the survivors. It’s easy to ‘second guess’ the motives and plans of those whose mountaineering accidents ends up as headlines in the press. There is an interesting article about RISK from a recent editorial in the NEW YORK TIMES.

In the grand scheme of things hiking and climbing are relatively ‘safe’ recreational pursuits. If we take Mt. Monadnock, for example, which sees about 100,000 hikers and climbers a year, there are only about a dozen injured that require a litter evacuation on an average year. That’s a 0.0012% odds of becoming injured while climbing Mt. Monadnock (about the same odds as being stuck by lightning). When compared with our odds of dieing in a motor vehicle collision (1.5%) it seems there are more risks in our day-to-day world that we take for granted than in mountaineering.

Some mountains around the world do carry more objective hazards than others. I found a few interesting lists where climbing or hiking on Mt Washington is not far behind the dangers of climbing Mt Everest!

Enjoy the great outdoors no matter what sport you prefer in New Hampshire’s outdoors. Expect the non-expected. Heed that small voice inside your head when you hear that, ‘LOOK OUT, STOP or TURN AROUND!’ And please don’t criticize too harshly the mistakes made that resulted in the above mentioned outdoor accidents. At least they were in the great outdoors and not laying on the couch.

“In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

Theodore Roosevelt